Improving the School Experience for Children and Youth with Refugee Experience

Schools play a key role in the settlement experience of newcomer children and youth. On this page, we summarize CYRRC’s recent research on students with interrupted formal education (SIFEs).

Learn more about these issues in our podcast episodes and policy brief on school supports.

What Challenges Do Children and Youth with Interrupted Schooling Face?

Students with interrupted formal education (SIFEs) refers to those who have had significantly interrupted, limited, or no prior school experience and who enter the school system with additional language, academic, and literacy needs.

Children and youth with interrupted schooling face multiple, interconnected barriers:

- Academic

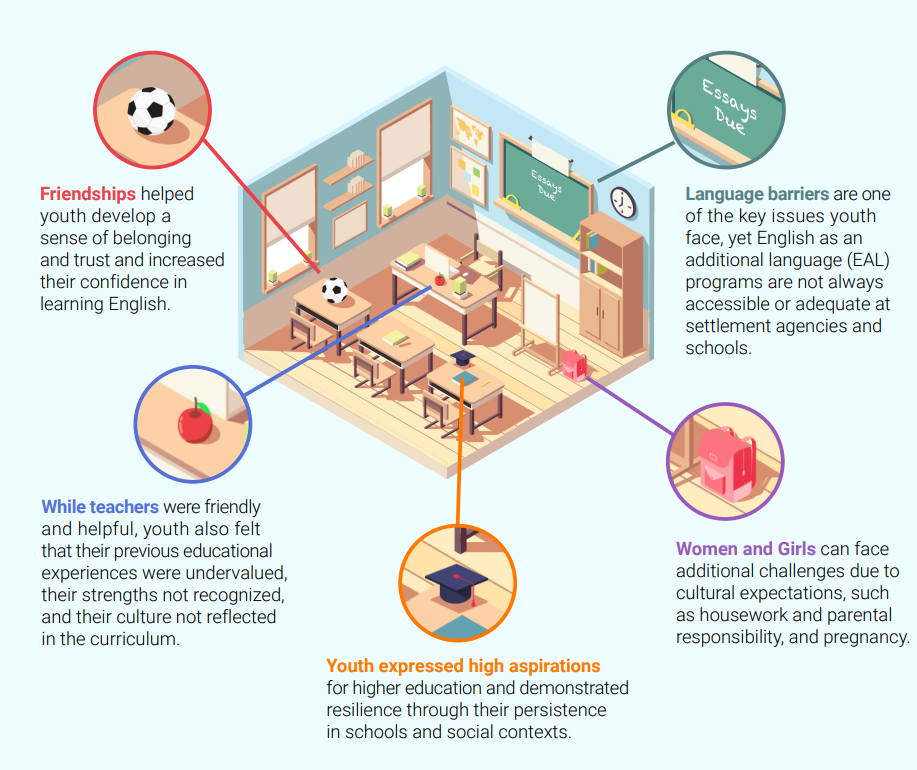

Language barriers are one of the key challenges that youth face. Yet English as additional language (EAL) programs are not always accessible or adequate at settlement agencies and schools.

Limited English language proficiency, academic gaps due to disrupted schooling, and grade placement based on age and English language assessment (rather than academic ability) are significant challenges for older youth. These youth may fall between the cracks as they transition or age out of high school.

Youth with refugee experience feel they are not reflected in the school curriculum, which was overly focused on European history and culture.

“[W]hen they came into the school system here in Nova Scotia, there was an assumption that they couldn’t handle a certain level of math, because they couldn’t speak English. So they were sort of treated like a one size fits all homogenous group, when in fact, they’re not they have different strengths. They have different needs. – Dr. Susan Brigham, The Refuge: Starting Over – Refugee Youth and Interrupted Schooling]

- Economic

The lack of economic resources affects youth’s ability to complete school. Many students are working full time to support themselves and their families.

- Psychosocial

Many SIFEs have experienced significant trauma. The process of overcoming traumatic experiences, acquiring a sense of safety, and adjusting to the expectations of a new culture impact their school experience.

Many families with refugee experience face persistent mental health issues and struggle with a lack of in-person support and a lack of mental health services.

“[O]ne of the things that we need to keep in mind is that a lot of the families and the children that come to school were forcefully removed from a familiar environment and having to settle in an unfamiliar community in school wasn’t their choice. So everything is not only new to them but it’s also strange … [They] also have a large amount of trauma and loss and grief that they bring. And sometimes, they may share it. Sometimes, they may not. But then with children, it may manifest itself in various aspects.” – Jayesh Maniar, Policy Matters – School Supports for Youth

- Gendered Differences

Women and girls can face additional challenges due to cultural expectations, such as housework and parental responsibility, and pregnancy. Meanwhile, boys —especially older youth who speak English— often quit school to become breadwinners for their families, resulting in a “power dynamic shift” among resettled families.

What Supports do Children and Youth with Refugee Experience Need in School?

There are a number of ways to improve the school experience of youth with refugee experience:

- Creating Supportive Learning Environments

Students with refugee experience are more likely to persist academically in school when they feel that their peers are open to diversity, such as being interested in their background, respecting them, and wanting to interact with them. Peer friendships can help youth develop a sense of trust and belonging and boost their confidence in learning English.

Students’ educational success depends on school environments that encourage diversity and teachers who support and encourage their students. Teachers play a key role in creating environments where students with refugee experience feel welcome and accepted. In order to address the needs of these students, teachers require support and training in English as an Additional Language (EAL) teaching, trauma-informed practices, and cultural responsiveness.

- Example: Creating a safe and caring classroom environment

An educator shared a teaching tool they used called, “While You Were at School,” where refugee students shared stories about what they were doing while age-equivalent Canadian students would have been in school. This activity helped the other students better understand the students with refugee experience and encouraged an openness to diversity.

- Supporting Educators and Settlement Workers

Teachers and service providers play a crucial role in supporting children and youth with refugee experience, however, there are several challenges that negatively impacted their ability to provide culturally relevant learning opportunities and supportive environments for all students:

- Their workload has increased as services and resources for refugees that were once provided are no longer available.

- They face challenges of reduced funding and staffing.

- They need professional development opportunities for working with students with refugee experience.

Improving the mental health of caregivers and service providers is important as it provides a foundation for children and youth’s socioemotional development.

- Collaboration

Collaborative relationships between educators, school staff, and local communities create opportunities for learning and addressing students’ emotional and psychological needs. Better coordination and collaboration among refugee service providers would allow complementary services to be identified and addressed.

“[T]here needs to be that cross-collaboration between government, between the education system, the schools itself and community … school divisions and teachers and administrators just have to be open to allowing community in the classroom and not just for language interpretation and not just for translation purposes. … I would highly encourage school administrators to seek partnerships with community organizations, with ethnocultural communities and with service providers that are helping parents, that are helping community members and just collaborate and provide spaces and provide hubs where continuous learning can happen and where those supports are being made available to our students. – Kathleen Vyrauen, Policy Matters – School Supports for Youth

- Resilience

Despite the challenges they face, students with refugee experience show high levels of resilience and many feel optimistic and grateful to attend school in their new country.

“[T]he youth themselves even though they are struggling to succeed academically they have also … shown resilience in term[s] of trying to adapt so they come also with their own strengths of facing the challenges that they are encountering.” – Reuben Garang, The Refuge: Starting Over – Refugee Youth and Interrupted Schooling

Recommendations:

- Consult with community partners to identify best practices for creating a culturally aware and competent school environment. Community partners should be welcomed into schools to reinforce the diversity of the communities from which newcomer youth come and allow opportunities for families to become more involved in students’ school life.

- Invest in professional development for teachers and school staff so that they can build trauma-informed practices and cultural responsiveness.

- Include requirements in Bachelor of Education programs to build competence in working with refugee children and youth.

- Schools should provide social spaces where newcomer youth can receive academic support and encouragement, as well as make friends. Provide additional funding to address transportation and other barriers to participation.

- Gender differences must be considered in education policy.

- Offer free and accessible English as an Additional Language (EAL) programs in a range from informal (e.g., public library programs) to more formal settings (e.g., within the school, as tutoring or formal classes).

- Hire teachers from a diversity of backgrounds to better represent the student population.

“[W]e hear it from students firsthand that they want to feel that connection to their teacher. They want to see themselves represented. They feel like they’ll be more comfortable to express if they have a need if it was somebody that knows what they’re going through.” – Kathleen Vyrauen, Policy Matters – School Supports for Youth

Explore the Research:

- Infographics

Brigham and colleagues “Refugee Youth and Interrupted Schooling” (2022)

Click to view infographic

Nakhaie, R., Ramos, H., & Fakih, F. (2022). School Environment and Academic Persistence of Newcomer Students: The Roles of Teachers and Peers. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 16(1), 64-84.